Aaron was born on the Summer Solstice and died on a random Saturday. He died in his spacious garage, its vaulted cathedral-like ceiling high above him. Perhaps he was working on one of his many beloved projects. Was he rebuilding the engine of a vintage VW Bug? Maybe woodworking beautiful cradles for a set of Massive GTX subwoofers? Or maybe syncing his stereo system to the winking headlights of a Transporter T2 bus cab, carefully severed from the rest of its body and wall mounted as a sculptural art installation? Only Aaron knows which project had his attention when, suddenly, and for no apparent reason, he went into cardiac arrest. Not a clogged artery. Not a faulty valve. Instead, a complete and final shut down of his heart’s electrical system. He was 61. A husband, father, grandfather, son, and brother. My brother.

Since Aaron passed, now months ago, I’ve found myself stuck in a loop of contemplation about his life, our relationship, and what it means to me to have lost him.

(Aaron’s subwoofer cradles; photo credit A. Johnson)

This experience of grief and grieving has involved contemplating both the particularity of Aaron’s life and death and the universality of life and death. Grieving Aaron’s death feels both deeply personal and existentially universal. As Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler (2005) write, “loss stands alone in its meaning to you, in its painful uniqueness.” They go on: “One person’s dying touches many people in many different ways; everyone feels that loss individually.” But, as we grieve particular losses and do so in particular ways, we necessarily confront the universal fact that everyone loses people they love, and everyone grieves such losses. Grieving for one special person opens a door to grieving for all. Once revealed, the truths behind this door are almost too existentially heavy to bear. Once in it, we might never exit the grief chamber.

Beyond the particular and universal, is sibling grief caught between additional pairs of contradictions? T.J. Wray, author of Surviving the Death of a Sibling (2003), writes that sibling relationships are “more complex than nearly any other, a mixture of affection and ambivalence, camaraderie and competition.” Continuing, she notes that, in terms of “the span of time, the intimacy, and the shared experience of childhood, no other relationship rivals the connection we have with our adult brothers or sisters.” Why wouldn’t the complexity of sibling relationships complicate sibling grief?

Sibling relationships are often framed by the contradictory truths of presence and absence. Especially for siblings close in age, we often cannot remember a time when we didn’t have each other in our lives. Typically for younger siblings, there was never a time when our older siblings weren’t there. Yet the formative intimacy of childhood often attenuates as we mature into our own selves and as our lives take their own shapes. Older siblings often push younger ones away to stake out their independence and pursue their own paths. They often leave home first, in a way abandoning their younger siblings. But, even in their absence, it often feels like they remain very present. Wray writes that there is a familiar comfort in simply knowing that our siblings are in the world.

(Aaron’s various projects; photo credit A. Johnson)

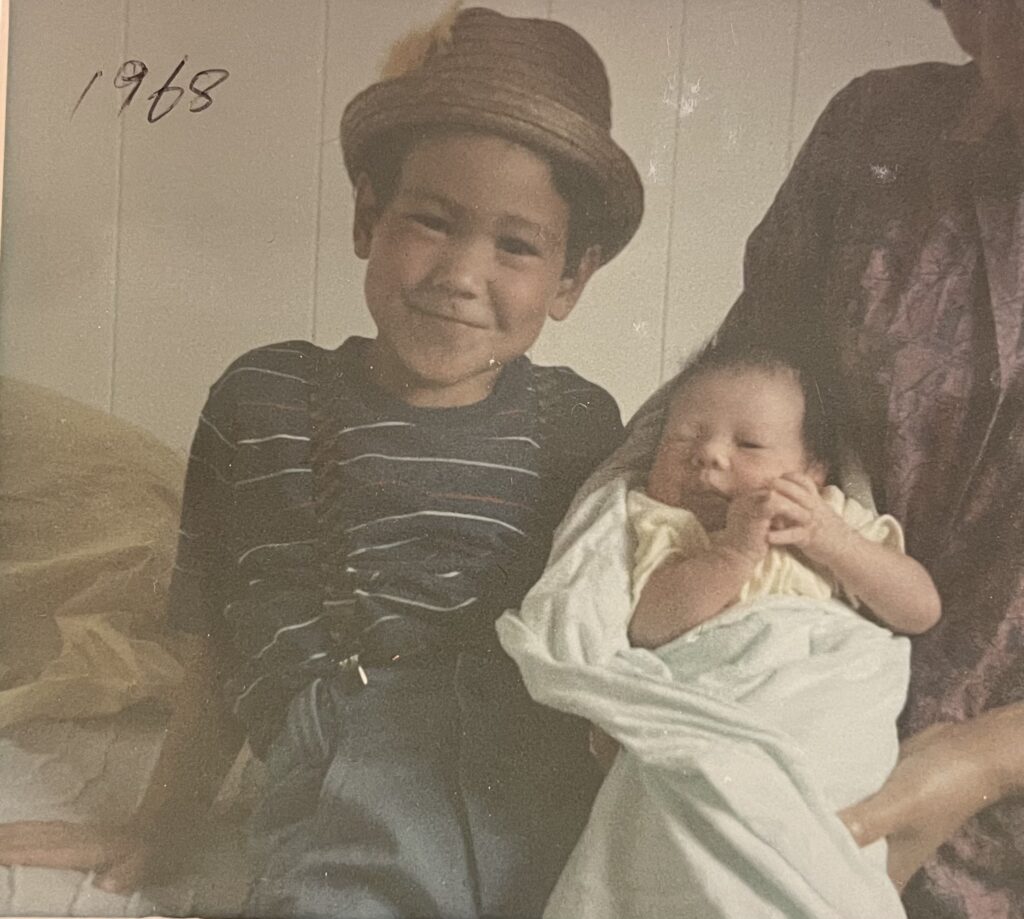

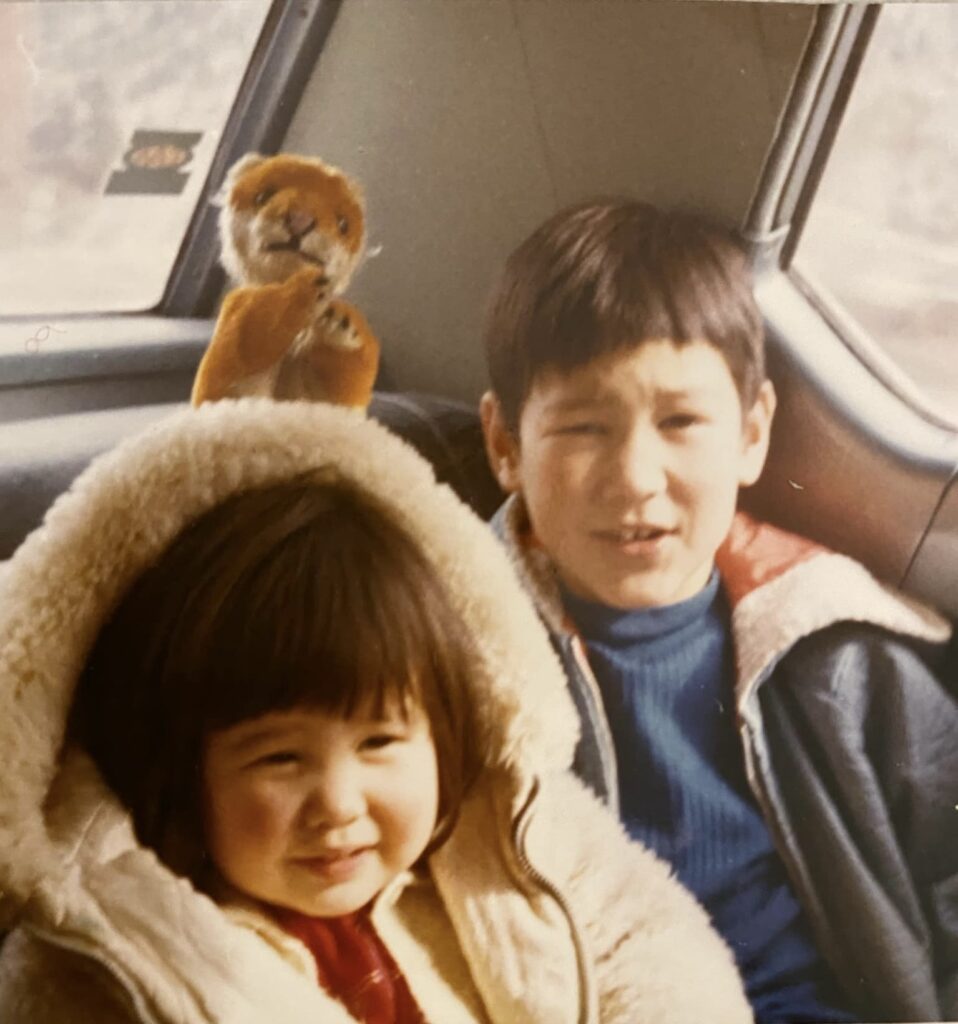

As I reflect on my relationship with my only sibling, I realize it’s not simply that Aaron has always had a presence but rather that he’s always been present in my life. He has actually been with me since my beginning – psychologically, intellectually, and emotionally. It’s not an exaggeration to say that I would not be me had he not been there with and, often, for me.

Aaron was five years older than me. From the beginning of my life, he knew what I needed and wanted. Before I could speak, he spoke for me. He put words to my experiences when I didn’t have them. He helped me develop my capacity for language. Eventually, he would teach me how to write my full name, our parents’ names, our address, and phone number.

More than communication with words, Aaron showed me how to express myself physically. My brother had a natural grace and athleticism. In school, he ran track, high jumped, played volleyball, road bikes, and skied. His movements were controlled and efficient but also graceful and relaxed; they were contained but also, in a way, transcendent. Watching Aaron at sports was to watch him tap into a harmony that seemed both within and beyond him. In my much younger days as a competitive then professional figure skater, I sought to emulate this kind of inspired movement. In recent years, I’ve sought this in longboard surfing. Aaron, without actively encouraging me, perhaps without even knowing it, gave me the desire and confidence to push myself physically and to excel at the sports I love.

Like many siblings, Aaron and I shared biological traits. The most apparent was our looks. We looked alike. It’s not that I found closeness to Aaron in our physical appearance. Rather it’s that how he looked enabled me to make sense of how I look. For many mixed-race people, our looks can be confounding, both to others and to ourselves. Growing up, I would often get asked: “What are you?” Indeed, I would respond silently, what am I? I’m not White, but I don’t look Japanese. So, what does that actually make me? Well into my adult life, I would have such conversations with myself. Looking at Aaron helped me understand my racialization and helped me accept my racialized identity not in terms of being half and half (hafu, in Japanese) but of being whole, sufficient, and beautiful. My brother was beautiful, and he helped me see my beauty. Being present in my life, Aaron helped me to better understand and accept myself. Yet as we were both launching our adult lives, he moved away and so did I. By our late-middle-age, we had spent vastly more years apart than we did together.

(Us over the years; photo credits M. Johnson, H. Kokubo, and M. Sakata)

There were other ways in which Aaron’s presence and absence helped frame my life. Aaron knew my weaknesses. He knew I was driven by an inferiority complex, plagued by anxiety, greedy for success, pathologically competitive, and arrogant. He knew my secret: I wanted, desperately, to prove myself.

Aaron never wavered in his support of me; he was proud of me. But, for himself, he lived very differently. He took his time in life. He cultivated and nurtured relationships, just as he hand-watered the fruit trees on his hobby farm. He was quiet, letting his senses take in life around him. On summer-time visits to our parents, he would sit on the warm stones at the edge of the lake, watching and listening, while the rest of us splashed around in the water. For others, this might have been a moment for “me time” to check social media or do Wordle. For Aaron, this quiet observation was an active way of being in and of the world. It was a way of absorbing into the world around him. Listening was a particular gift of his, which served him well in his personal relationships and in his car stereo business. He loved people, food, VWs, and music, and he let his senses soak it all up. He never tried to be anyone but himself. In his gentle way, Aaron was truly remarkable.

My brother did not judge me and my more obsessive ways. But he was always present, showing me an approach to life much more in harmony with oneself and with others. From as far back as I can remember, he showed me that, by slowing it down, letting go, and just being, everything would be alright.

(Aaron’s radishes, hothouse, and bread; photo credit A. Johnson)

Aaron and I never talked about any of this. How can a relationship be so profoundly formative yet marked with so much silence? How could we have been so close yet so distant?

Kübler-Ross and Kessler note that you cannot force grieving. You can’t simply exit the loops of denial, anger, regret, and depression. The contradictions of Aaron’s presence and absence help me accept grieving for him as a process of rumination about him. In this light, I’m able to lift my gaze up the walls of grief and let my senses take in the beauty of life and love. The days are longer now, the Solstice is approaching, and this is what my big brother would want for me.

(My brother Aaron; photo credit P. Gibbons)